The other humans: The emerging story of the mysterious Denisovans

The existence of the Denisovans was discovered just a decade ago through DNA alone. Now we're starting to uncover fossils and artefacts revealing what these early humans were like.

TODAY, there is only one species of human alive on the planet. But it wasn’t always so. For millions of years, and until surprisingly recently, there were many types of human-like groups, or “hominins”. They coexisted, perhaps they fought, and they interbred. It would be fascinating to know how these others lived, but understanding who they were and what they were like is extremely challenging. We cannot put ourselves into their minds, and we have only fragmentary clues from fossils and artefacts they left behind to reconstruct their lives.

That challenge is especially daunting for one of these extinct groups, the Denisovans. Discovered just a decade ago, the Denisovans have left us scant physical evidence. Instead, our knowledge of them comes almost entirely from their preserved DNA. It tells us that they are a sister group to the Neanderthals, that they lived in Asia for hundreds of thousands of years and that they interbred with our species. But we don’t know what they looked like, how they walked or if they could speak.

Now, that is changing. In the past few years, archaeologists have alighted on a few fossils that seem to be Denisovan. They have also unearthed treasure troves of artefacts, including tools, jewellery and even art, that they think were created by these mysterious people. These interpretations are potentially explosive, so it is hardly surprising that some dispute them. Nevertheless, we are starting to piece together a picture of the Denisovans, one of our closest cousins, and a group that still lives on in the DNA of many people today.

The discovery of the Denisovans came as a total surprise, partly because it played out differently from the uncovering of every other extinct human group. The story starts in the Altai mountains in southern Siberia, Russia. For decades, archaeologists have been excavating in Denisova cave – named after a hermit called Denis who lived there in the 18th century. Hominins have inhabited it on and off for hundreds of thousands of years. Most were Neanderthals who, although most prevalent in Europe and west Asia, sometimes made it as far east as the Altai.

In 2008, archaeologists led by Michael Shunkov at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Novosibirsk discovered a fragment of finger bone in the cave. Assuming it belonged to a Neanderthal, Shunkov sent it to Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Pääbo’s team extracted DNA from the bone and found it didn’t match Neanderthal DNA – or modern human DNA. It was something never seen before. After initially referring to the individual as “X-woman”, Shunkov and Pääbo settled on “Denisovans” as a name for the group.

The findings were published in 2010. Never before had a group of hominins been identified solely from its DNA. Another surprise was to come, however. Some of the Denisovan DNA sequences matched those found in people living on the islands of Melanesia, especially Papua New Guinea. The implication was that thousands of years ago, Denisovans and members of our species, Homo sapiens, had sex and produced children. As a result, today around 5 per cent of the DNA of Melanesian people is Denisovan, with many of these genes appearing to play key roles in immunity to diseases.

In itself, the interbreeding wasn’t too big a shock. Pääbo’s team had published the sequence of the Neanderthal genome earlier in 2010, revealing that H. sapiens and Neanderthals interbred, and that all humans today whose ancestral group developed outside Africa carry some Neanderthal DNA. But the Denisovan interbreeding was odd because their DNA was found thousands of kilometres away from Papua New Guinea in Denisova cave. The implication was that Denisovans were once widespread. In fact, their “demographic and evolutionary core” was probably in south Asia, says Jean-Jacques Hublin, also at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

This was all based on DNA from a single finger bone. There was no skeleton, and no artefacts. The Denisovan people themselves were a total mystery. A study published in 2019 sought to address this by using the Denisovan genome to deduce what they looked like. Researchers identified methyl “tags” attached to the genome, which reveal how active each gene was, and used that information to generate an image of a Denisovan face. However, the study was widely disputed, not least because nobody has ever even shown that methyl tags can “predict” the appearance of a known species.

If the genome cannot tell us what Denisovans looked like, we must find out the old-fashioned way – by excavating Denisovan remains. To that end, people have been exploring sites in China and nearby countries, and scouring old museum collections. For almost a decade, there was nothing. Now there is.

This was all based on DNA from a single finger bone. There was no skeleton, and no artefacts. The Denisovan people themselves were a total mystery. A study published in 2019 sought to address this by using the Denisovan genome to deduce what they looked like. Researchers identified methyl “tags” attached to the genome, which reveal how active each gene was, and used that information to generate an image of a Denisovan face. However, the study was widely disputed, not least because nobody has ever even shown that methyl tags can “predict” the appearance of a known species.

If the genome cannot tell us what Denisovans looked like, we must find out the old-fashioned way – by excavating Denisovan remains. To that end, people have been exploring sites in China and nearby countries, and scouring old museum collections. For almost a decade, there was nothing. Now there is.

The oldest known bracelet, dated to 45,000 years ago, was found in Denisova cave

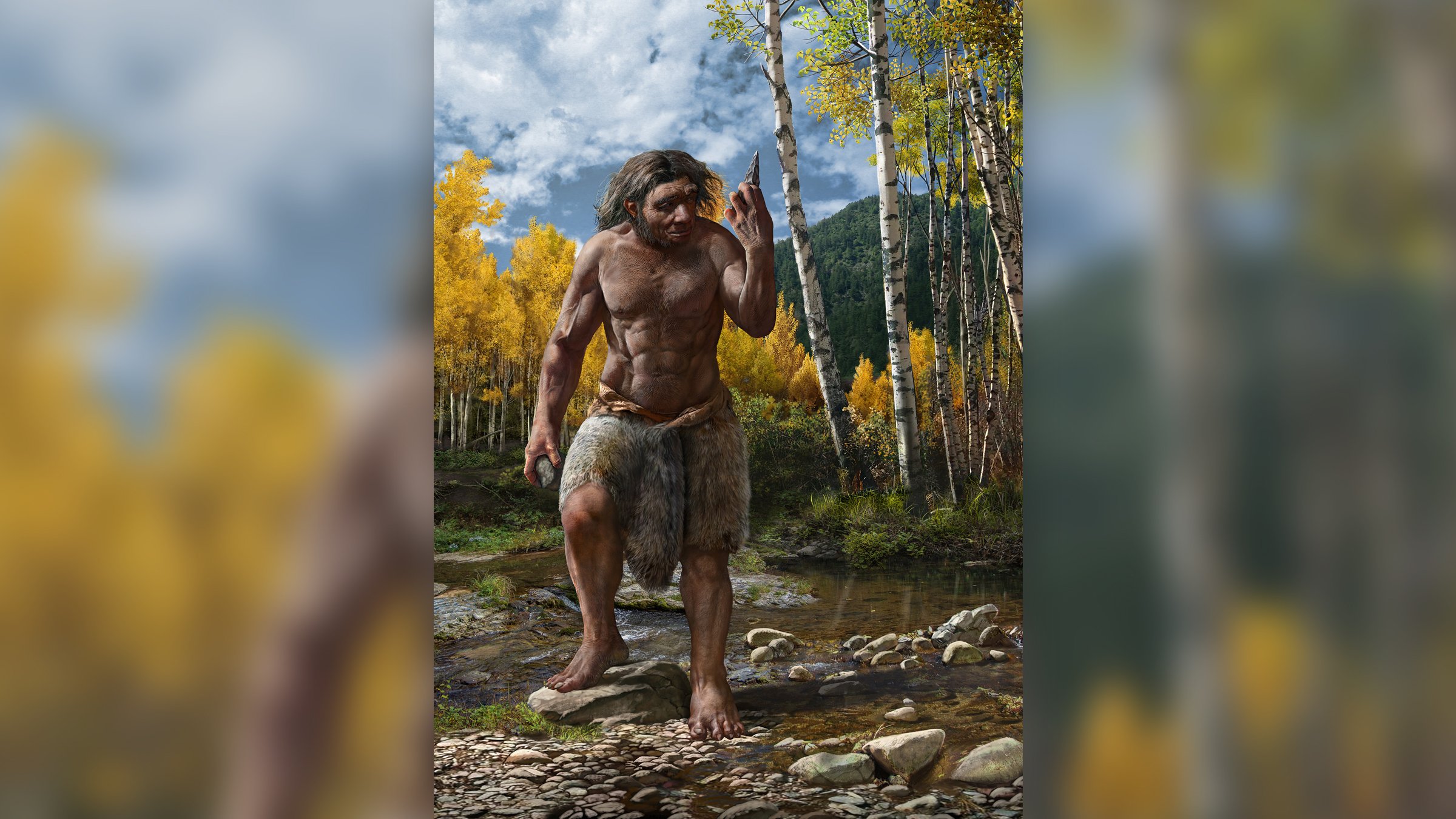

Bence Viola, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Toronto in Canada, has found several skull fragments in Denisova cave. Details haven’t been published yet, but viewing a cast of one over Zoom reveals that the bone is unusually thick. To Viola, this suggests that Denisovans were big – perhaps more than 100 kilograms – with “American football player body build”. Analysis of their genome reveals it contains DNA from an unidentified older population: could they have interbred with the decidedly bulky Homo erectus, a species that lived on in east Asia long enough to have met them?

High society

These fragments are the best Denisovan fossil evidence found so far at the cave, but archaeologists have expanded the search. A crucial clue emerged in 2014. Emilia Huerta-Sánchez now at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and her colleagues were studying a gene called EPAS1, which is involved in the body’s response to low oxygen levels. People living on the Tibetan plateau, more than 4 kilometres above sea level, have a modified version of EPAS1 that helps them cope with the thin air. Huerta-Sánchez found that this came from interbreeding with Denisovans about 43,000 years ago.

Denisova cave is only 700 metres above sea level, so it seems unlikely that the mutation arose there. But it would have been a useful adaptation if Denisovans were living at high altitude elsewhere. Tentative evidence of this emerged in 2018. At Nwya Devu on the Tibetan plateau, a research team found thousands of stone tools buried between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago that might have been left by Denisovans – or H. sapiens.

More compelling evidence comes from Baishiya Karst cave in Xiahe in the north-east of the Tibetan plateau. It is a sanctuary for Tibetan Buddhists and, in 1980, a monk meditating there found a jawbone. “Local people used to collect bones in this cave to grind, to make some kind of medicine,” says Hublin. “Luckily, this monk did not grind the fossil.” Instead, it was sent to Lanzhou University in China. It doesn’t contain any preserved DNA, but, in 2019, Hublin and his colleagues revealed that they had managed to extract protein from one of the teeth. This matched protein found in Denisovans. They also concluded that the jawbone was at least 160,000 years old.

Many people found it hard to accept that Denisovans were living in one of the harshest environments on Earth 160,000 years ago. But, in October 2020, researchers led by Qiaomei Fu at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, China, reported finding Denisovan DNA preserved in the sediments of Baishiya Karst cave. The DNA samples dated from 100,000, 60,000 and possibly also 45,000 years ago. Not only were the Denisovans there, it looks as if they were there for at least 115,000 years, plenty of time to evolve adaptations like the modified EPAS1 gene. “I was a little more sceptical in the beginning,” says Viola. But the sediment DNA sealed the deal. “I’m really convinced.”