The Earliest Unequivocal Evidence of Our Species May Be Even Older Than We Realized

The course of human evolution never did run smooth. The emergence of hominins on the continent of Africa is full of twists, turns, gaps, and dead ends, which makes it all the more difficult to retrace the rise of our own species.

The Omo Kibish Formation in southwestern Ethiopia. (Céline Vidal)

Today, we still don't really know when or where the first Homo sapiens appeared on the scene, although an archaeological site in southwestern Ethiopia is one of our best lines of evidence.

It was here, in the 1960s, that paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey uncovered the earliest examples of fossils with undisputedly modern human anatomies.

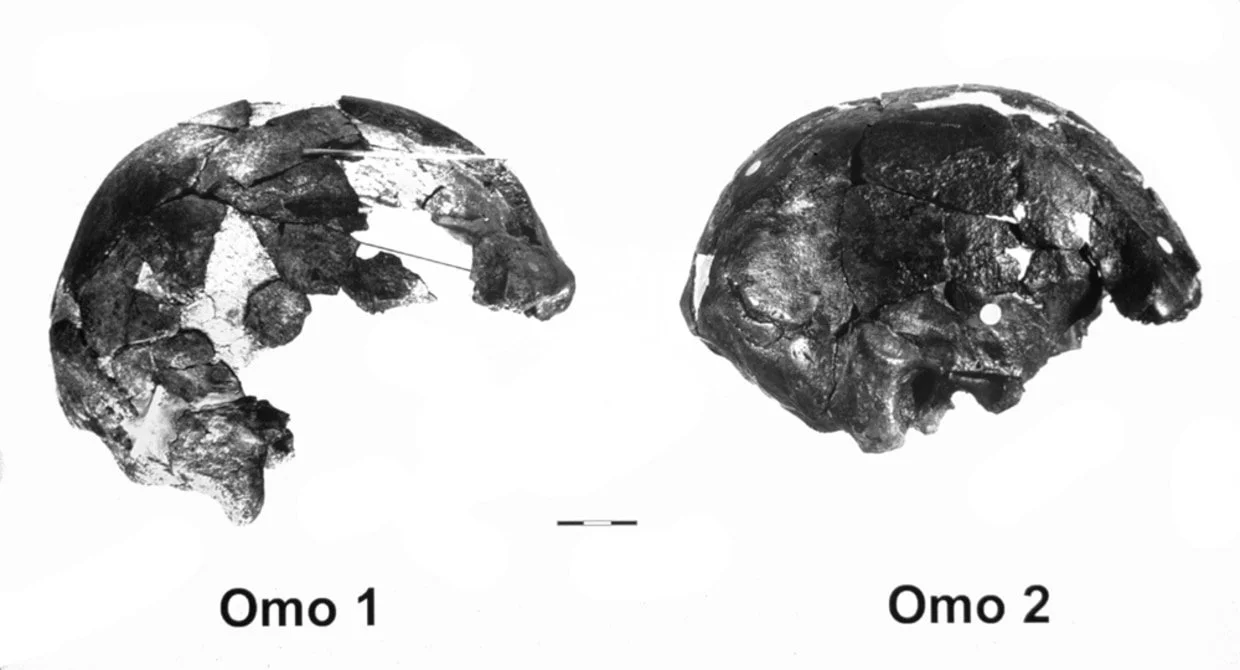

To be clear, older remains attributed to Homo sapiens exist, dating back hundreds of thousands of years. But the line between us and our ancestors is a smear of characteristics, leaving us with the remains known as Omo I as a starting point for what is unequivocally modern.

The ancient bones of this long lost ancestor, named for the nearby Omo River, were buried with mollusk shells, which were, at the time, dated to about 130,000 years of age.

In the decades since, radioactive dating of the surrounding soil has allowed us to push back that age even further to about 200,000 years. And yet even that could be an underestimation.

A geochemical reanalysis of the archaeological site now suggests Omo I was squashed between two layers of volcanic ash, the upper layer of which was probably deposited in an eruption about 230,000 years ago. At the very least, researchers argue, Omo I must be even older than that.

"The fossils were found in a sequence, below a thick layer of volcanic ash that nobody had managed to date with radiometric techniques because the ash is too fine-grained," explains volcanologist Céline Vidal from Cambridge University.

Omo I Distal Femur (upper bone in knee joint).jpg Two pieces of a femur -- the leg bone immediately above the knee -- from an early human known as Omo I. Both pieces were found in Ethiopia's Kibish formation. The bottom piece was found in 1967, when scientists believed it was 130,000 years old. The top piece was found in 2001 as part of a study published in the Feb. 17, 2005 issue of the journal Nature. In the study, scientists from the University of Utah and elsewhere say Omo I actually lived about 195,000 years ago -- the earliest known member of our species Homo sapiens.

"When I received the results and found out that the oldest Homo sapiens from the region was older than previously assumed, I was really excited," she recalls.

The new estimate solidifies Omo I as the oldest unchallenged Homo sapiens in Africa. And while this suggests Ethiopia was a cradle for our species more than 230,000 years ago, other early humans were already using the continent as their nursery at this time.

In 2017, researchers announced they had found ancient human remains in Morocco that were dated between 280,000 years to 350,000 years of age.

The skulls found here are more elongated than ours today, with slightly larger teeth, which has led some scientists to suspect these were not Homo sapiens, but rather an 'archaic' species of human that spread to North Africa before our more direct ancestors arrived to replace them.

DNA analysis of these ancient Moroccan fossils has not been successful, which means we don't know how related they are to our own species.

An analysis of genes taken from the remains of a boy who lived just before migrations dramatically reshaped the genes of African populations several thousand years ago also hints at an ancient split of at least 260,000 years ago.

Where this split occurred is a whole other matter. Judging from the fossil record, East Africa is an important hub for human evolution, but for all we know, there could be an even older human like us hiding somewhere else on the continent.

The hunt for our heritage continues.

The study was published in Nature.